SOMALIA'S

DEGRADING ENVIRONMENT

Causes

and Effects of Deforestation and

Hazardous Waste Dumping in Somalia

An

essay prepared for a PhD course of 'Environmental Systems Analysis & Management'

given by the Division of Industrial Ecology, KTH. The essay is presented at

a final seminar for the course, on 11-12 June 2001 in the division.

ABDULLAHI ELMI MOHAMED

B.Sc., M.Sc. Lic.Eng. Ph.D. Candidate at the Department of

Civil and

Environmental Engineering, Royal Institute of Technology (KTH), 100 44 Stockholm

SWEDEN. E-mail: elmi@kth.se

General

Environment [1] is increasingly becoming an important issue in the world politics and global economy as well as people's life. Environmental deterioration [2] is now a global issue - ecologically, economically, politically [3] - that require global solution (Elliott, 1998). Today, the most notable environmental problems in the world include global warming leading to climate change, water pollution contributing to human health problems, deforestation resulting desertification, destruction of species, ozone depletion, increasing urban and industrial wastes, etc. Human activity and life is changing the environment in ways, on scale, quite unlike in any other era, making our common future [4] in jeopardy. Environmental problems occur in the interaction between two complex systems, the human-society system and the ecological system. However, to preserve security [5], the entire human environment[6] is taken into consideration (Graeger, 1996).

Large percentage of people's illness in poor countries is directly linked to the pollution of their natural environment. Improved environment resulting improved public health is therefore a clear element in the struggle and the strategy of poverty eradication. In general terms, population growth, economic development and growing inequality in income all put greater pressure on the ecosystems. Moreover, poverty [7] and political conflict, whish are the features of most developing countries, also cause environmental damage. Environmental degradation increases the poverty of those who are already poor especially in those parts of the world where livelihoods and lives are closely dependent on natural environment (Elliott, 1998). Globally, deforestation and illegal hazardous waste dumping, among other abuses, are human conducts bankrupting natural resources of future generations.

The Scope and the Purpose of the Paper

Somali is by no means an exception in the above situation. There are substantial challenges of environmental concerns in the country, which is far less studied. The country suffers from almost all types of environmental degradations. In one hand, Somalia is experiencing enormous environmental problems, while on the other hand it is lacking both human and financial resources as well as political stability to address these life affecting issues. In view of these above-mentioned situations, the paper will concentrate on describing and analyzing the subject in relation to Somalia. It will particularly focus on legal and moral aspects of deforestation and hazardous waste dumping in the country. The purpose of the paper is to discuss and shed some light through analysis on deforestation and illegal hazardous waste dumping in Somalia. As methodology, literature and document review, information gathered from relevant organizations was carried out.

Background to Somalia

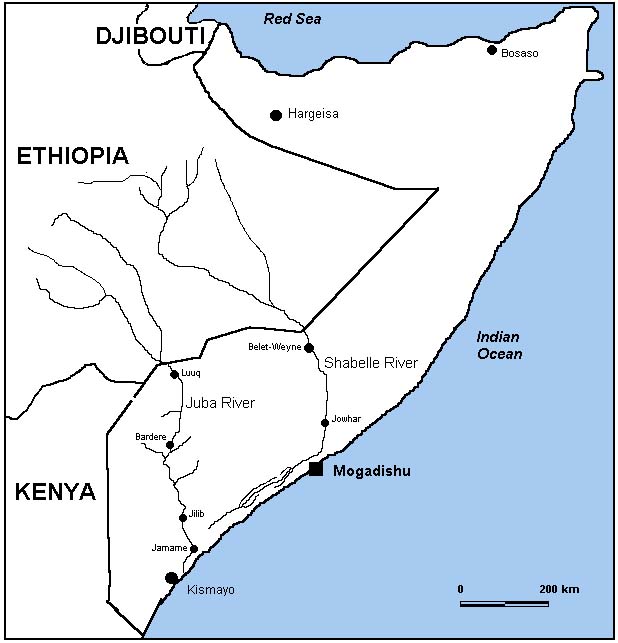

Located in the Horn of Africa, adjacent to the Arabian Peninsula, Somalia is geographically located in a very advantageous region, bordering both Indian Ocean and the Red Sea. Country's land area is estimated to 637 660 sq. km. It shares borders with Kenya, Ethiopia and Djibouti, as shown in the figure below.

The modern

history of Somalia constitutes about 120 years (1880-2000): 80 years (1880-1960)

of colonial rule (Lewis, 1988) and division; 30 years (1960-1990) of democratic

but mostly military rule and; 10 years (1991-2001) of chaos and State collapse.

The widespread famine [8] in Somalia in 1992-93

caused by low agricultural yield due to several years of droughts combined

with bloody civil war has resulted the largest UN humanitarian efforts and

peacekeeping operations in history. Despite being politically disintegrated,

Somali has culturally and ethnically homogenous society. Poverty, which together

with injustice is threatening the integrity of the nation, is the major root

of social conflict and cause of the current political crisis in Somalia.

The country has an estimated population of about 9 million in 1995, of which

75% in rural areas [9]. Rate of population growth

is about 3%, while Mogadishu is growing by a rate of 10% a year (World Bank,

1995). Agriculture is the second traditional occupation for most Somalis,

after nomadic livestock [10] grazing/raising.

Livestock and banana export is country's two principal revenue generating

sectors. Somalia has one of the lowest human development index (HDI) in the

world.

Physical Environment

Most of the country is typically sparse savanna with few forested areas. According to the World Band, 55% of Somalia's land area is suitable for grazing, while the FAO estimate is lower, 29%, but still shows the greater for livestock production. Official estimates of Somalia's forest cover refer to 52,000 hectares of "dense" forest and 5.7 million hectares of "low density wood" (Somalia, 1987, ch. 7), this means that 9% of the total land is low density woodland - savanna woodlands. This is to indicate country's limited amount of wood resources, which mainly consist of Acacias trees. On the other hand, Somalia has the longest coastline of Africa, which stretches a distance of about 3300 km in both the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea. The long coastline is of importance chiefly permitting trade with the Middle East and the rest of East Africa.

Historical and Ongoing Country's Environmental Concerns

Somalia

is currently experiencing almost all types of environmental concerns, both

natural and man-made.

Natural Environmental Problems:

Indicating the level of water scarcity, rainfall is very low (250 mm/y) and

variable, while the potential evaporation is extremely very high (over 2000

mm/y). Droughts that occur very frequent are naturally caused by climate.

It leads to water shortage and starvation particularly for the rural communities,

which are more dependent on rainwater and grass for their survival in livestock

raising and cultivation traditions. Being a natural disaster, drought causes

loss of life both human and animal every year in Somalia. Deadly droughts

is often followed by devastating floods, another natural disaster, which mainly

severely affects southern part of the country, where the two rivers, the Juba

and the Shabelle, flow. These recurrent drought and severe floods affect the

lives of the people and their animals without prediction and prevention.

Man-made Environmental Problems:

Human-induced environmental abuses include: water pollution contributing to

human health problems; alarming deforestation and overgrazing resulting desertification

and soil erosion; salinisation by inefficient irrigation destroying valuable

productive land; illegal fishing and industrial toxic waste dumping in the

sea and coastline areas by outsiders; improper disposal of human and solid

waste by local people affecting the public health; hunting and extinction

of wildlife; and degradation of coastal zones. Increasing population living

along the coastline put a significant pressure on coastal aquifers for freshwater

supply. Vast marine resources are under unprecedented threat from overexploitation

of fish resources and hazardous waste dumping activities by outsiders.

No

Environmental Agency Ever Established:

Despite of these major concerns, no central (governmental) coordinating body

charged with environmental protection exist, even prior to the collapse of

the state in 1991. However, several ministries and state agencies were concerned

with protection and management of the environment as part of their function

during the period before the civil war. National Parks Agency was established

in 1970 for the purpose of establishing parks and reserve area. There was

no however a single protected area listed in the country as late as 1991 (UNEP,

1993). The National Range Agency, founded in 1976, was empowered, inter alia,

to establish grazing and drought reserves, and to prevent and control soil

erosion on the range.

Among the limited range of concrete steps taken was the prohibition in 1969

of charcoal and firewood export, in order to protect trees. This was amended

in 1972 to give a monopoly of charcoal exports to the National Commercial

Agency [11]. Prior to the state collapse, the

Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources, founded in 1977, was responsible

for prevention pollution of the sea. However, the capacity to control the

long coastline was always lacking and no control of pollution has even existed.

2. DEFORESTATION in Somalia

Deforestation - The Result of Charcoal

Charcoal [12] plays an important role in both the energy sectors and the economies of most African countries. Charcoal making provides a considerable amount of employment in rural areas; it also allows for a quick return on investments. However, the inefficiencies inherent to the production and use of charcoal place a heavy strain on local wood resources, resulting severe environmental consequences. In many parts of the world, the use of charcoal has been blamed for deforestation [13]. Deforestation in the drier parts of Africa has led to an even worse problem - desertification and the loss of thousands of species. Deforestation is the product of the interaction of many environmental, social, political, economic and cultural forces at work in any given region.

SOMALIA - Deforested Country

During the last several years, a new type of business was introduced in Somalia. Cutting of trees to produce charcoal for export to the Gulf States has become a big business with considerable profits. In order to optimize the operation, local businessmen introduced a new technology - battery-powered chain saws for cutting of the forests. Trees are cut down, burn and brought by trucks for export from major ports in the country, particularly Mogadishu, Kismayo and Bosaso (BBC, 2000; and local newspapers) [14]. Becoming Somalia's black gold, traders earn about $US million per ship (IRIN, 2000). Most of the charcoal is made in southern Somalia, while northern and eastern regions also experience the same problem but to a lesser extent. More than 80% of the trees used for charcoal are types of Acacia, the most dominant species (IRIN, 2000). Due to absence of government, there is no documentation of the volumes being exported or the amount of trees being cut down.

Causes Behind the Conduct

The alarming rate of deforestation has a number of combined causes behind it. It is evident that it is largely a combination of human activities and social conditions.

Charcoal

for Urban and Firewood for Rural:

Somalia has the lowest consumption of modern forms of energy in the Sub-Saharan

Africa[15]. Firewood and charcoal are the major

sources of energy for the majority of the people in Somalia. As a result of

this, the removal of trees in Somalia is steadily increasing, following demographic

trends, which are reversing the traditional Somali nomadic way of life, as

well as other social crisis. As their source of energy, rural people rely

on firewood while urban inhabitants use charcoal. Mogadishu's charcoal supply

comes mainly from the south. In rural areas, strong link between poverty and

deforestation exist. Like other countries in Sub-Sahara Africa, Somalia is

presently, as well as in the past, suffering from energy problems. Power and

fuels cut-off have been frequent in all urban centers, access to electricity

have also been poor or unreliable, if not absent.

Potential

Energy Resources - Un-exploited Sources:

Yet Somalia is rich in energy resources, having un-exploited reserves of oil

and natural gas, untapped hydropower, extensive geothermal energy resources,

many promising wind sites, and abundant sunshine, which can produce solar

power. Despite all these, traditional biomass fuels - mainly firewood and

charcoal, the smoky and inefficient fuels of the poor - account for 82% of

the country's total energy consumption (Makakis, 1998 p.74). Technically,

it would not be problem to develop these potentially available energy resources.

Major obstacles are today political, financial and institutional.

Foreign

Demand for Charcoal - the Major Driving Force:

Traditionally, the making of charcoal was limited to a small group of cutters

who used hand axes and responded to an internal and very localized demand,

which during the last several years started to increase. In spite of increases

in local consumption, foreign demand for charcoal puts unprecedented pressure

on locally limited wood resources. Taking full advantage of country's lawless

condition, interest-driven local businessmen[16]

with commercial links in the Gulf countries export tremendous amount of charcoal

to mainly Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Charcoal from dry land

in poor Somalia is used in the houses of the Gulf countries as luxurious.

Lack of Government - An Opportunity for Outsiders:

Being without government since 1991 when the former regime was overthrown,

Somalia is the only country in modern history of the world which lacked central

government so long[17]. Since then the country

is ruled by a series of rival warlords each holding a small territory of the

country. This created a condition which the country became stateless vulnerable

for anyone's exploitation particularly outsiders and local self-interest-driven

individuals. This lack of functional system of government and control facilitated

these individuals to run these unsustainable business activities damaging

local natural environment. Lack of government in Somalia could therefore be

seen as the major cause of the ongoing deforestation.

The

Issue of Land - Legal Perspectives:

Institutional arrangement that specify rules, rights and obligation for the

use of natural resources are called property rights regimes [18]

(Bromley, 1991; Hanna, 1999). During the rule of the last regime (1969-1991),

government have tended to try to increase their control in land previously

owned collectively by the communities in the rural areas. This was done through

shifting the land-ownership from communal to state in pursuit of revenues.

By the 1975 Land Law, all land in Somalia is nationalized. The new Law demands

mandatory land registration which traditional landholders resisted. Consequently

this has progressively limited local rights rather than supported. As the

state authorities lacked capacities to manage and control the nationalized

land, this legislation (of making the land a state property) made the land

no man's land with open-access type of property-rights regime [19].

The effect of that 1975 Land Law is therefore highly relevant for the ongoing

land degradation. After the state collapse in 1991, the result became the

creation of 'ownerless' land with open-access to anyone's exploitation which

accelerated, among other abuses, the rate of deforestation. The land property

which the state of Somalia had claimed as its own and which the rulers had

exploited during the military regime now became fair game for the new power

brokers. Now as the people increase dramatically and some of the land naturally

and antropogenically became degraded, new land with life-supporting-resource

are required. Struggle for such a land thus became one of the major sources

of the present conflic [20]. Common resources,

such as forest, which is free and open for all, tend to be vulnerable to depletion

and degradation due to overuse and misuse, this is commonly referred to as

"the tragedy of commons" (Hardin, 1968).

Adverse Environmental Consequences of Deforestation

The illegal

removal of trees in Somalia to produce charcoal for export is an action destroying

the common national capital, which the society does not benefit. Although

public awareness of the impact of the deforestation in Somalia has increased

in recent years through media, it has not slowed the alarming rate of deforestation

appreciably. As a result of deforestation, land suitable for grazing is destroyed.

This will inevitably affect the nomadic communities who entirely depend on

grazing. The most visible results of this action are desertification, soil

erosion, and general environmental degradation. The highest price will be

the long-term effect in desertification [21] .

The valuable role of trees in controlling runoff and water and the positive

interaction of acacias with crops and animals are reasons why much more emphasis

needs to be given to the forest protection. Deforestation will have major

adverse impacts on rainfall availability, capacity of the soil to hold water,

local climate, and habitat for animal species and bio-diversity. Basically,

humans abandon areas that have been cleared, particularly when the community

is nomadic depending on grazing for their animals. All these will finally

collectively affect the livelihood and socio-economic aspect of the society.

In addition to environmental impacts, deforestation as an income-generating

activity also causes internal dispute and conflict within the society. In

1997, actions taken by local chiefs and clan elders in areas in central Somalia

who tried to prohibit charcoal cutting led to conflict, that resulted loss

of life (IRIN, 2000).

3. ILLEGAL HAZARDOUS WASTE DUMPING in Somalia

Hazardous Waste and Illegal Dumping

World's chemical industries and nuclear energy plants[22] have already generated millions of tons of hazardous wastes[23]. Industrialized countries generate over 90% of the world's hazardous wastes (WCED, 1987). The high growth of industries in developed countries was accompanied by an equally high increase in the production of toxic hazardous wastes. But the technological capacity to handle these by-products - wastes, was not developing by the same level. This is the reason why problem of these wastes, particularly nuclear wastes, still remains unsolved. Taking advantage of political instability and high level of corruption but lured by the potential financial gains, poor African nations [24] have been used as the dumping sites for hazardous toxic waste materials from developed countries. In some cases, the income generated from this trade, of importing hazardous waste from the West, have exceeded the GNP of many poor countries. Poverty is the reason of accepting importation of toxic wastes [25] . Bearing the cost of the damage caused by the hazardous wastes, Africa disbenefit the entire attempt of generating revenue to alleviate poverty. This do-or-die method become an alternative solution to the desperate search for revenue for some African countries, which are ill-equipped to dispose these health and environment threatening wastes. Both the exporting and importing counterparts violated international treaties to which most countries in the world are signatories.

SOMALIA - World's Most Attractive Illegal Hazardous Waste Dumping Site

During the Somali civil war, hazardous wastes were dumped in industrialized countries. In the fall of 1992 reports began to appear in the international media concerning unnamed European firms that were illegally dumping hazardous waste in Somalia [26]. What caused controversy in 1992 were reports of a contract established by European firms with local warlords. The alleged perpetrators were Italian [27] and Swiss firms who entered contracts with Somali warlords and businessmen to dump waste in the country.

Investigations

by the UNEP

In a news release statement (Tolba, 1992) by then executive director of

the UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme) situated in Nairobi, Dr. Mustafa

Kamal Tolba, it became apparent that the European firms was disposing a hazardous

waste in Somalia. The UNEP started to investigate the matter five years later

in 1997 and hired Mahdi Geddi Qayad[28] as a

team leader (for a period of one month) to carry a field investigation in

many areas of Somalia particularly coastal zones. The outcome of the investigation

(a report) was not published but an Italian newspaper has succeeded to receive

a copy of the report.

Familgia

Cristiana - an Italian Newspaper

Familgia Cristiana - an Italian Newspaper, has published several articles

about the issue during 1998 (Familgia Cristiana, 1998). Based on the UNEP

investigations as well as its own investigation, the newspaper gave relatively

a detailed description. Familgia Cristiana (1998c) showed a map over the country

particularly areas where wastes have been dumped and pictures taken from places

where signs of the dumping could still be seen. According to the newspaper,

waste dumping concentrated both in coastal zones and inland areas. Naming

several individuals both Somalis and foreigners who involved in the waste

transport, the newspaper disclosed many secrets in the business both in terms

of deals made and health impacts on local people. In an $80 million contract

in late 1991, two Swiss and Italian firms, Achair Partners and Progresso,

would be allowed by senior local politicians at the time to build a 10 million

ton storage facility for hazardous waste at the rate of 500 000 tons a year.

Although the major part of the waste dumping in Somalia occurred after the

state collapse in 1991, the activity has started even during the former regime

in 1989 (Familgia Cristiana, 1998d).

According to the newspaper, there are ongoing dumping activities inside the

country, and Mr. Halifa Omar Darameh of the UNEP said "our concerns are

the negative consequences that these dumping can cause in the immediate future,

and it is unfortunately impossible to safeguard a long coastline of

3 300 km long".

Parliamentary

Report

In view of these serious waste dumping allegations against the Italian

and Swiss firms, the Italian Parliament demanded a study on the issue. A commission

has been established. The final report (produced in 2000) of the parliamentary

study said the so-called "Eco-Mafia"[29]

run companies dealing with 35 million tons of waste a year, making $US 6.6

million. According to the report, radioactive waste from Italy dumped in Somalia

may have affected Italian soldiers based there with a UN force in the mid-1990s.

The report also disclosed that the Mafia controls about 30 percent of Italy's

waste disposal companies, including toxic waste, according to a parliamentary

study.

Why Dumping in Somalia

Several European companies are engaged in the business of dumping industrial

and chemical wastes in Somalia. The relevant question is why is it that waste-dealers

and importers ignore the long-term effect and obvious dangers associated with

illegal dumping of toxic wastes in poor countries. But the more relevant question

is why dumping in Somalia? Reasons that made Somalia world's most attractive

waste dumping site are many and below are the most likely ones:

- Country's political situation: Since 1991 Somalia is lacking a central government that can safeguard its long coastlines and large territories. This seems to be the most likely reason that attracted the waste-dealers to use Somalia as a dumping site for the waste generated elsewhere.

- The need to find

dumping site: Generally, there is a big problem of finding suitable dumping

sites within the countries generating these wastes, as there are few areas

left there. By finding a cheap site, the high costs of recycling, incinerating

and disposing in original country could be avoided. According to a study

by American University of Washington (1996), the cost of disposing one

ton of hazardous waste in their source of generation was estimated to

US$ 3000 and as low as US$ 5 in a developing country

[30].

- Geographical Location:

Located in a very geographically central location, It is easy to reach

Somalia. This reduces the cost and the time of waste transport.

- Low public awareness

about the dumping: During these years local people are in civil war associated

social problems, which made them busy in their life affairs. Local media

was not so effective. There were also fears of talking about the issue

in the media.

- Local self-interest individuals: It was easy to establish local contacts (politicians and businessmen) who are ready to allow the dumping of these toxic waste in their home country despite the long-term effects of the dumping on the local people, in only exchange for a relatively enormous amount of money in foreign currency, in a short period of time. This facilitates the disposal process.

Negative Environmental Consequences and Impacts on Related Issues

The effects

of hazardous wastes dumped improperly on both human and other environmental

components are inestimable. According to the newspaper (Familgia Cristiana,

1998), UNEP investigations and local people, the health effects so far identified

are enormous. These include (i) the death of fisherman in the town of Brawe

after opening a small container collected from the sea, (ii) the death of

several people living the along the coastline who drunk water in a container,

(iii) the increase of patients with cancer in Somalia, which were related

to the toxicity of the wastes dumped in the country. In addition, a study

made by an Algerian expert explained the link between the recent years' increase

in livestock's death and the toxic waste dumping in the country. Dr. Pirko

of the UNICEF said that the town of Bardere experienced unknown disease that

caused the death of 120 people after suffering noise bleedings. This was also

related to the toxicity. Premature births that occurred were due to the high

toxicity of the dumpsite.

However, no research has been carried out on the existing and the potential

environmental and social impacts of the waste dumping. The negative long-term

impacts are expecting to be huge particularly pollution of the groundwater

and fish resources, which will inevitably affect the overall public health

and the entire socio-economy of the country.

International Legal Instruments of Hazardous Wastes

The issue of waste dumping in Somalia is twofold in that it is both a moral and legal questions. First, it is ethically questionable to dump a toxic waste [31] in a very poor country in the midst of a protracted civil war with no central government. Being against moral principles, these conducts are beyond humanity and games played on the lives of innocent people. Second, there is a violation of international law in the export of hazardous waste to Somalia. Below are the international and regional laws regulating the waste transport.

The

Basel Convention

The Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements [32]

of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal is a broad and significant international

treaty on hazardous waste. It was adopted in 1989 and entered into force on

May 1992. The Basel Convention, ratified by 135 countries, is the response

of the international communities to the problems caused by the ever increasing

toxic wastes which are hazardous to people and the environment. Italy and

Switzerland, whose private firms have been accused to dump waste in Somalia,

are parties to the Convention, while Somalia is not. Regulating the transboundary

movement of hazardous wastes and providing obligation to its parties to ensure

that such wastes are disposed of in an environmentally sound manner, one of

the main principles of the Convention is that the hazardous waste should be

treated and disposed of as close as possible to their source of generation.

In addition, the Basel Convention urges that the generation and movement of

hazardous waste should be minimized.

OAU

Ban on Waste Transport

Equally important and with more regional significance was the voting of a

resolution by the Organization of African Unity (OAU) to ban member countries

from accepting industrial waste products. Half of members of the OAU are non-signatories

of the Basel Convention. Despite the OAU's attempt to ban such trade, member

countries have violated the ban. The reasons for doing so are based on economics;

the need to generate substantial amounts of revenue to alleviate the economic

hardships faced by Africa.

4. CONCLUSION

This paper

gave an overview of Somalia's degrading environment, particularly the ongoing

deforestation and illegal hazardous waste dumping during the last decade.

Since the state collapse in 1991, country's environmental degradation has

accelerated, especially the rate of deforestation has steadily accelerated

while toxic waste dumping became newly established business. Because of the

country's political condition and the lack of central system of government,

many foreign private companies, which are taking full advantages of the lawlessness

and lack of central government in Somalia, started to either plunder or pollute

country's natural resources. These opportunistic activities started immediate

after the state collapse. Both deforestation and illegal toxic waste dumping

in Somalia became evident after the disintegration of the country into clan-based

areas following the overthrown the dictatorial military regime in 1991.

No research at any level has been conducted in Somalia, concerning the deforestation

as well as the hazardous waste dumping. Particularly, the amount of waste

dumped, the number of trees cut down and their environmental, economic and

social impacts. As deforestation will affect more than forests, the remaining

forest reserves need to be protected.

Charcoal export has become a big profitable business for local businessmen

and their clients in the Gulf countries, who deliberately take full advantage

of Somalia's lawless condition. The rate of deforestation in many parts of

Somalia is alarming. These deadly business activities run by narrow-sighted

self-interest individuals.

Taking Somalia as a case study, the paper indicates how poor countries in

the developing world became targets for the Eco-Mafia dealing with the international

traffic of toxic wastes generated in industrialized countries. Searching for

cheaper ways to get rid of the wastes, the Eco-Mafia establishes local contacts

especially irresponsible politicians and self-interest businessmen. European

private firms particularly Italian and Swiss has been accused of illegally

dumping hazardous wastes in Somalia during the last decade. This illegal and

immoral trade of charcoal and waste dumping are done in the knowledge of what

the consequences are for the country. This is one of the worst things currently

happening in Somalia's natural environment and very high price for will be

paid in the future. Through illegally dumping toxic waste from industrialized

countries and foreign induced deforestation, Somalia's natural resources of

future generations are bankrupted and plundered for profit. These merciless

damages to Somali's natural environment are legally and morally unacceptable.

These cases are just a few, which demonstrate the ineffectiveness of global

attempts to regulate an industry that overshadow its very hazardous impacts.

The lack of laws to protect the environment is nowhere as evident as in Somalia.

Apart from charcoal and hazardous waste dumping; illegal fishing, merciless

hunting, water pollution, are all environmental abuses that have gone unchecked

in Somalia for over a decade. The threat and damage done to Somalia's environment

will not receive the attention it merits as long as peace and political stability

remain the main life-threatening conditions in the country. In its totality,

the damage done to Somalia's natural environment is unimaginable and seems

unmanageable even long after a solution is found for the current difficult

prolonged political crisis.

Magnitude of water and environmental crisis and problems facing Somalia during

this newly began century is unprecedented. The protection of Somalia's coastal

zones from hazardous waste dumping and land from deforestation requires technological

and organizational capacity as well as political stability sadly lacking in

the country.

In terms of international law and moral principles, illegal dumping of hazardous

waste is crime, particularly in areas where wastes are not originated and

in poor people's land. As over-exploitation, misuse, destruction and pollution

of natural resources are transgression against human existence and their natural

environment, international as well as regional legal instruments regulating

the illegal waste dumping are in place. Somalia has the legal right to be

compensated what ever damage which the waste dumping and foreign-driven deforestation

caused to the country.

Footnotes

[1] The term 'environment' is probably the most widely used in contemporary science but there is no consensus

on what it means. However, for the purpose of this paper, the environment is considered to be a comprehensive term

that includes both human and physical factors such as water, soil, vegetation and air as well as animal populations.

[2] Environmental degradations is one of the major causes of civil unrest in the world.

[3] World's biggest summit, otherwise known as Earth Summit or Rio Conference, is the UN Conference on Environment and

Development held in Rio de Janeiro in Brazil in June 1996, attended 178 national delegations and many others.

[4] Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED, 1987), known as Bruntland Commission.

[5] With the end of the cold war, the breakdown of the 'military-security order' and the increasing knowledge of ecological

systems and the effects of environmental degradation, a new security concept has begun. This resulted in a change from a

focus on military security to environmental scarcity and security.

[6] This, Human Environment, was the title of the first international conference on environment held in Stockholm, 1972.

It was described as the event where international debate on the environment began (Tolba, Al-Kholy et al, 1992).

[7] Those who are poor and hungry will often destroy their immediate environment in order to survive (WCED, 1987:28).

[8] Because of the adverse effects of the famine, which forced the people to eat animal skin, Somalia was at that time

described in the media as the hell on the Earth. The world was also watching living skeletons on the TV coverage.

[9] These estimations are based on the population census in 1987 (i.e. 7 million), but it seems that the civil war during 1990s

may have caused a real reduction in the population size and growth. Data on population is however lacking.

[10] The livestock is estimated to about 40 million (Somalia, 1988). Somalia rank third in the world in terms of pastoralist

population size, and it is home to the largest camel population in the world (Markakis, 1998). In the country, camels are

mobile searching for water and grass, which are naturally rare. They contribute to nation's overall economy.

[11] Recently established Transitional National Government (TNG) of Somalia in Mogadishu announced on 22nd of

February 2001 that forest cutting and animal hunting should be stopped. This announcement was released on the

STN Radio of Mogadishu by the Minister for Livestock, Forestry and Range.

[12] Charcoal production: The carbonization of wood is brought about by heating it to temperatures high enough for it to

undergo substantial thermal decomposition. Temperatures reached in the process are usually in the range 400500°C

and a mixture of gases, vapors and a solid residue (charcoal) results. The temperature reached in the production

process has a marked influence on the composition and yield of the charcoal produced.

[13] Grainger (1992) defined the deforestation as 'the temporary or permanent clearance of forest for agriculture

or other purposes. Other purposes could be such as firewood, charcoal making, building , material etc. According

to this definition, if clearance does not take place then deforestation does not occur

[14] On February 2000, QARAN PRESS of Mogadishu reported that the largest amount of charcoal was shipped

from a natural port of Jasira outside Mogadishu by local businessmen. Uncountable Lorries loaded with charcoal

were lining up in a queue occupying in an extremely long distance of the roads of the city on their way to the port for export.

[15] Annual consumption of modern forms of energy in Sub-Saharan Africa is the lowest in the world (Davidson and Karekezi, 1993).

[16] Greedy rich (in urban areas particularly with international commercial links) also destroy the environment more

than the hungry poor (Goodland, 1991: 25). In view of environmental resources available for human beings, this fits

into the Mahatma Gandhi's statement "there is enough for our needs but not for our greedy".

[17] After 10 years of collapse, the Somali State government is, however, now re-established at the Peace

Conference in neighboring country of Djibouti, where a Transitional National Assembly (a Parliament) and an interim

President were elected in August 2000. Due to the current conditions, it has not yet become functional and recognized.

[18] Common-property resources may be held in one of the four basic property -rights regimes (Osmon, 1990;

Feeny et al. 1990; Bromley, 1989). These are State property, Communal property, Private property and Open-access property.

[19] As freedom in the commons brings ruins to all (Hardin's notion, 1968), open-access is the absence of well-defined property rights

[20] The ongoing civil war in southern Somalia was described as a struggle for land (Besteman and Cassanelli, 2000)

[21] But the traders laugh this off. "I remember as a child watching the cutters chop down trees in my area, and if you go back there now

to the same place, the trees are even bigger than they used to be", declared one trader. "There will be no shortage of charcoal" he said (IRIN, 2000).

[22] Today the world has over 450 plants of nuclear energy production. Of this, 108 are in USA and 150 in Europe.

[23] Hazardous waste is the waste, which is not destined for productive use, but for disposal.

[24] These include Benin, Djibouti, Guinea-Bissau, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone and Somalia (Alessandra,

Jennifer and Shehu, 1993). The trade on waste dumping in Africa started already in 1970s. UNEP estimates

that as much as 20% of hazardous waste trade goes to developing countries (Murphy, 1994).

[25] At the Lome negotiations, Benin gave detailed explanations arguing importation of wastes had to do with survival.

[26] See The Guardian (September 11, 1992); European Information Service (September 12 and October 6, 1992); BBC Somalia Branch

(September and October 1992); Agence France Presse AFP (September 14, 1992); Inter Press Service (September 10, 11, 24, and 30, 1992);

Saudi Gazette (September 13, 1992); Chicago Tribune (September 11, 1992); Reuters Limited (September 11, 1992); Somali Local Newspapers in Mogadishu. According to the local people, the waste was seen being dumped off the Somali coast into the Indian Ocean.

[27] Italy produces between 40 and 50 million tons of industrial wastes and 16 million of household wastes each year (Alessandra,

Jennifer and Shehu, 1993).

[28] Mahdi was a former associate professor at the Dept of Chemical Engineering of the Somali National University.

[29] Eco-Mafia is a new type of international businessmen trading on the transportation of industrial wastes generated in the

developed world. Being self-interest group, Eco-Mafia transgress international laws regulating such a trade.

[30] But the study did not take into account the environmental and social costs in the developing countries in the future.

[31] A toxic waste that is generated from a natural resource whose benefit has been used elsewhere than Somalia.

[32] The term Transboundary Movement is adopted when the transportation and disposal of hazardous waster are done across international frontiers

REFERENCES

Agence France Presse (AFP),

1992. "Italy Denies Export of Toxic Waste to Somalia." September

14, 1992.

Alessandra, Jennifer and Shehu, 1993. Nigeria Waste Imports From Italy. Trade

Environment Database (TED) Case Studies, Volume 2, Number 1, January, 1993.

See in the web http://www.american.edu/projects/mandala/TED/nigeria.htm

BBC Somalia Branch, (Octoober) 2000. Correspondence by Nuur Shire Osman in

Puntland, Garowe.

BBC Somalia Branch broadcasted on September and October 1992. London.

Besteman, Catherine, and Cassanelli, Lee, V., (eds.) 2000. The Struggle for

Land in Southern Somalia: The War Behind the War. Haan Associates, London.

Bromley, D. W., 1991. Environment and Economy: Property Rights and Public

Policy. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Bromley, D. W., (ed.), 1992. Making the Commons Work: Theory, Practices, and

Policy. San FRancisco: ICS Press.

Chicago Tribune, (September 11) 1992. "Toxic Waste Joins Somalia's List

of Woes"

Davidson, O. and Karekezi, S. 1993. 'A New, Environmentally Sound Enery Strategy

for the Development of Sub-Saharan Africa, : In S. Karekezi and G. A. Mackenzie

(eds), Energy Options for Africa: Environmentally Sustainable Alternatives.

London: Zed Books.

Elliott, Lorraine, 1998. The Global Politics of the Environment. New York,

N.Y. New York University Press.

European Information Service, 1992. "Italy Demands Inquiry on Toxic Waste

Dumping in Somalia. September 12 and October 6, 1992.

Falkenmark, Malin; Jan, Lundqvist, & Carl Widstrand, 1989. Macro-scale

Water Scarcity Requires Micro-scale Approaches: Aspects of Vulnerability in

Semi-Arid Development. Natural Resources Forum. Vol. 13,no. 4. Pp. 258-267.

Familgia Cristiana, 1998a. Somalia: UNA PARTITA TRUCCATA. N8 published on

4th

March, 1998. See http://www.stpauls.it/fc98/0898fc/0898fc18.htm,

Familgia Cristiana, 1998b. Somalia: Commercia di armi, stive pienne di rifiuti

tossici, traffici vecchi e nuovi: E LA NAVE VA.. N13 published on 8th April,

1998. See http://www.stpauls.it/fc98/0898fc/0898fc18.htm,

Familgia Cristiana, 1998c. Somalia: IL TRAFFICO CHE UCCIDE. N47 published

on 29th Nov., 1998. See http://www.stpauls.it/fc98/4798fc/4798fc84.htm.

Familgia Cristiana, 1998d. Somalia:QUEI TRAFFICI DI ARMI E SCORIE, La testimonianza

di Franco Oliva, collaboratore della Farnesina. See http://www.stpauls.it/fc98/0898fc/0898fc22.htm

Feeny, D., F., Berkes, and B. J. McCay, 1990. "The Tragedy of the Commons

Twenty-two Years Late.Human Ecology 18:1-19.

Goodland, Robert, 1991. Tropical Deforestation: Solutions, Ethics, Religions.

Environment Working Paper No. 43, World Bank, Washington, D.C., 1991.

Grainger, A., 1992. Controlling Tropical Deforestation. London. Hanna, 1999

Hardin, G, 1968. The tragedy of commons. Science 162: 1243-1248.

Inter Press Service, (September, 10) 1992. "Somalia: European Firms Dumping

Toxic Wastes, UNEP to Probe".

Inter Press Service, (September, 11) 1992. "Somalia: Italy Under Fire

for Toxic Dumping Reports."

Inter Press Service, (September, 24) 1992. "Somalia: OAU Concerned Over

Toxic Waste Dumping."

Inter Press Service, (September, 30) 1992. "Somalia: EC says it Can not

Stop Toxic Waste Dumping in Somalia".

IRIN (UN Integrated Regional Information), 2000. Focus on Charcoal Trade in

Somalia. Released on October 25th , 2000.

Graeger, N., 1996. "Environmental Security". In Journal of Peace

Research, vol. 33, no. 1, 1996, pp. 109-116.

The Guardian, 1992. "Italian Firm Denies Somali Waste Deal". September

11, 1992.

Lewis, I. M. Modern History of Somalia.

Local Newspapers include QARAN PRESS; XOGOGAAL; SAHAN; BANAADIR during 1997,

1998, 1999 and 2000.

Murphy, Sean, 1994. Prospective Liability regimes for the transboundary movement

of hazardous wastes. American journal of international law., vol. 88 no. 1

January, pp. 24-75..

Osmon, E., 1990. "Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions

for Collective Action." Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Poaletta, Michael, 1993. "Somali Waste Imports from Europe and Civil

War". Trade Environment Database (TED) Case Studies, Volume 2, Number

1, January, 1993. See in the web www.american.edu/projects/mandala/TED/somalia.htm

Reuters Limited (September 11, 1992). Switzerland asks UN help on Somalia

Toxic Waste Links."

Saudi Gazette, (September 13 1992). "Somali Allows Toxic Waste Dumping."

Somalia, 1987. Five Years National Development Plan 1987-1991. Mogadishu:

Ministry of National Planning. ch. 7.

Tolba, Mustaba. Kamal, 1992. "Disposal of Hazardous Wastes in Somalia".

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) News Release, Statement by UNEP

executive director, 9 September 1992.

Tolba, Mostafa Kamal, Osmana A. Al-Kholy et al, 1992. The World Environment:

1972-1992: two decade of challenge (London: Chapman & Hall).

UNEP, 1993. Environmental Data Report 1991-1992. Nairobi: UNEP. p.198

WCDE, 1987. Our Common Future. p2, 226.

World Bank. 1985. Somalia: Agricultural Sector Review. Washington. DC: World

Bank.

Makakis, John, 1998. Resource Conflict in the Horn of Africa. PRIO. International

Peace Research Institute, Oslo.